An aquifer must be porous (contain void spaces) so that it can store water, and permeable (the gaps must be well connected) to allow the water to flow through the rock. This means that only certain rock types are suitable. The best aquifers are coarse-grained sedimentary rocks in which the grains are spherical and all about the same size.

When the grains in a rock are all spherical and around the same size they can only pack together loosely because they can’t squeeze into spaces once they are touching their neighbours. This leaves a large amount of void space (pores). Larger grains lead to larger pore spaces. The pores will also be quite well connected, so fluid can flow easily between them.

Conversely, a wide variety of grain sizes allows the grains to pack together more tightly because small grains can fill gaps between the larger ones, thereby decreasing the porosity. The gaps will also be less well connected and fluid will take longer to seep between pores. If grains are angular they also have more potential to squeeze into small gaps, so angular grains will tend to lead reduce porosity and permeability.

Mineral ‘cement’ between grains helps to hold the rock together but also fills up pores and connecting channels, reducing porosity and permeability. Therefore, a coarse, poorly cemented sandstone with spherical grains makes a good aquifer while a well-cemented rock containing only fine grains or one containing coarse, medium and fine grains makes a poor aquifer.

Where Do We Find Aquifers?

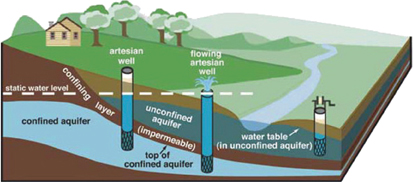

Rain seeps down through the Earth’s crust, effectively ‘filling up’ the rocks overlying the impermeable deep layer. Rocks with poor permeability can reduce the downward percolation of water, so the replenishment of water in an aquifer may be inhibited by an overlying impermeable rock layer. In this case, if the aquifer reaches the surface at some point water can be replenished at that location and, from there, flow through the rest of the layer.